By Steven Soifer, Ph.D., M.S.W.

CEO, International Paruresis Association

Chairperson, University of Memphis Department of Social Work

Published and copyrighted by the International Paruresis Association, Inc. 2012

Dr. Soifer’s contact information:

ipasteven@gmail.com

sdsoifer@memphis.edu

901-678-2615 (office)

Introduction

While it’s hard to believe, it’s been over a decade since our book Shy Bladder Syndrome: Your Step-by-Step Guide to Overcoming Paruresis (2001, New Harbinger) was published. The book has sold over 17,500 copies — not a bestseller, but not bad, either. (I’ve heard that in some circles 20,000 in sales is considered a bestseller.) While the book is in its 10th printing, the publisher will not agree to issue a 2nd edition, which I tried to write on the 10th anniversary of its publication. So, after having thought about it for a year, I’ve decided to write an update to the book in E-book format, so that crucial information about this social anxiety disorder can be disseminated.

I thought a lot about how to do this E-book; in the end, my decision was to follow the format of the original book, which would make it easier to write another edition in the future. This book is not a substitute for the 2001 version; I am assuming that everyone reading this E-book has already read Shy Bladder Syndrome. If not, I would highly suggest doing so first. In the interest of succinctness, I am not going to repeat the information found in the original book.

Hopefully, anyone reading this book is also familiar with our websites: www.paruresis.org; www.shybladder.org; and www.americanrestroom.org. There, additional information will be found about this social phobia, which we estimate now affects 21 million people in the U.S., and approximately 220 million people worldwide.

If you, the reader, have any questions about the material in this E-book, I suggest you email info@paruresis.org, and we will attempt to respond to you in a timely manner. Meanwhile, happy peeing!

Steven Soifer, Ph.D., M.S.W., CEO, International Paruresis Association; Co-Director, Shy Bladder Center; Secretary, American Restroom Association.

Page 1

I. What is Shy Bladder Syndrome (Paruresis)?

By now, most know that shy bladder syndrome (known also by the medical term paruresis) is a social anxiety disorder that is obliquely referred to under Social Phobia (300.23) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV-TR of the American Psychiatric Association. However, what we didn’t know a decade or more ago (though I suspected it early on) is that paruresis is also an example of a chronic pelvic floor dysfunction, which can be measured using an electromyography (EMG) device.

Dr. David Gordon, a neurologist who practices at Chesapeake Urology Associates in the Baltimore area, has tested five people (including me) using the above-mentioned device and discovered that four out of five of us had abnormal EMG readings. Thus, we have the “smoking gun” to prove that this is not all in our heads. (Of course, as we know, our affliction is clearly a classic mind-body problem.)

There are three other reasons I’ve suspected over the years that there is a physiological basis for our disorder. First, occasionally I would hear from someone that he had his prostate removed due to cancer, and lo and behold, his paruresis cleared up. Second, occasionally someone would have Transurethral Microwave Therapy (TUMT) for benign prostate hyperplasia, and he too would see an improvement in his paruresis. (Though at times, I’d get a report from someone that this procedure didn’t help.) Finally, a couple of people have gone the route of getting a Botox injection in their pelvic floor, and if (and it’s a big if) the right set of muscles were paralyzed, relief in symptoms from paruresis would be reported for up to six months (however, in at least one case, the reverse effect was achieved, producing a bout of incontinence for awhile). Paruresis, then, is a pathophysiological condition in which our symptoms are a result of various processes going on in the body, the cause of which is not clear at this point in time.

Page 2

However, the way I describe this in workshops is that somewhere along the line, we experienced a short-circuit in our peeing mechanism, and when we try to urinate when other people are around us, the “system” does not fire properly, and we cannot pee for the life of us.

I believe that over time, we may actually find out that there are different subtypes of paruresis, each caused by a different “pathway,” the end result being the same. Nonetheless, at this point in time, given the paucity of research into our affliction, we are stuck with simply knowing that we can’t pee in certain situations and that for many of us, that’s a huge pain, both figuratively, and occasionally, literally.

In our original book, we presented a very simple scale for assessing if one has paruresis. Over the last decade, progress has been made in refining scales for measuring this social phobia. Probably the best has just been released by Deacon et al (2012), which I describe in more detail in the literature review section of this manuscript.

Finally, I think it is fair to say that it is most useful today to look at shy bladder syndrome as a “continuum” or “spectrum” disorder, much like autism has been reframed. Thus, many people (perhaps close to half the population?!) occasionally have difficulty peeing, whether due to an actual physical problem, a medication-induced one, or “temporary” stage fright of the bladder. However, in none of these situations does the person catastrophize the incident, and it slides off them much like butter in a Teflon frying pan. But, for perhaps 7 percent of the population, paruresis starts becoming an “obsession,” and s/he begins to have trouble peeing around other people. This feeds on itself, and the person can develop a full-blown case of the disorder. Still, it ranges in severity from being a minor nuisance to dominating a person’s life. The most severe case would be someone who becomes functionally agoraphobic due to this condition. For those in whom paruresis develops badly enough, we can say this person suffers enough that s/he meets the criteria of social phobia in the DSMIV-TR. The bottom line: it

Page 3

significantly interferes and/or impairs one’s life. When it gets this bad, people often will seek treatment, either individually, through a shy bladder workshop, or by some other means. Many are pushed into treatment when a “crisis” occurs in their life concerning this problem, such as drug testing in the workplace, needing to travel for business or pleasure, or changes at work or home that create uncomfortable peeing scenarios.

One final note: since we wrote the original book, it is my observation that paruresis is much more widely known across the U.S., and perhaps even globally. Here’s what I’ve seen: there is a more general awareness among the population at large (to wit: a Saturday Night Live 35th season-opening parody commercial on the subject), easy access to information about the problem (thanks primarily to Google and the evolution of the Internet), a younger generation (under 30 – Gen Y) much more comfortable talking about it, more mental health treatment providers aware of the disorder (but not necessarily knowing how to treat it), and much more media coverage of the topic.

However, the one area in which I feel little, if any, progress has been made is with the medical community in general and the urological community in particular. I am still appalled at how few medical practitioners know what to do when a patient presents with this problem. Later on, I will explain what I think needs to be done about this problem.

Page 4

II. The Underlying Mechanism of Paruresis (by David Gordon, M.D. & Gregory Nicaise, M.D)

Micturition Overview

The ability of the bladder to expel urine is known as voiding. The inability to voluntarily void is known as urinary retention. Successful voiding occurs as a result of the interactions of all three components of our Central Nervous System (CNS). These are the sympathetic, the parasympathetic, and the somatic nervous systems.

Before we can understand the neural interaction involved in voiding, we must first understand the anatomy of the bladder and the bladder outlet. The bladder is an organ located deep in the pelvis. It is essentially a hollow muscle (the detrusor), not unlike the heart. Its function is to fill with fluid (urine) in increasing volumes at low pressures until the viscoelastic properties of the detrusor muscle are met. At this time, the bladder will need to empty or void. During this filling phase, the bladder muscle must stay relaxed or stable, that is, there can be no intrinsic bladder muscle activity.

Interestingly, there is another series of muscles involved in the storage and voiding cycle. These are the sphincteric muscles located at the proximal urethra and the bladder neck area. There are two main complexes: the Internal Sphincter (IS) and the External Sphincter (ES). Just as the detrusor muscle must stay relaxed during the filling phase, the IS and the ES must be contracted. The combination of a relaxed detrusor muscle working alongside a contracted sphincteric complex (IS & ES) is what maintains continence.

In contrast to the detrusor muscle, the IS, or bladder neck muscle, must remain contracted (closed) during filling. However, when bladder capacity is reached and the detrusor prepares to contract, the IS must then relax in a coordinated fashion to allow for bladder emptying. The actions of the IS are accomplished without direct voluntary control.

Page 5

The external sphincter (ES) surrounds the urethra, 1 – 3 cm distal to the IS, which is located at the bladder neck. It is an annular structure composed of both striated and smooth muscle. The ES complex is under both voluntary and involuntary (autonomic) control. The inner smooth muscle ring operates involuntarily, while the outer striated ring (aka rhabdosphincter) is under voluntary control. It is the voluntary relaxation of the ES that acts as the trigger for coordinated bladder muscle contraction and volitional voiding.

Neural Control Synopsis

Urine is an ultrafiltrate for the blood. The filtration process occurs at the level of the kidneys and drains into the bladder anatomically via the ureters. Bladder filling is modulated by tension receptors known as baroreceptors in its wall. These baroreceptors are connected to unmyelinated sensory nerves, which interpret filling volumes based on detrusor muscle tone. At this point, the neural control of voiding may take one of two pathways depending on the age of the subject. Essentially, there is an Infantile Neural Network and an Adult Neural Network, the latter of which takes over after the long spinal tracts are myelinated. This usually occurs before the age of five years. If the Infantile Neural Network is selected, the subject is basically operating through a simple sacral reflex arc. Here, once bladder-filling information reaches a certain volume and tone, the information is translated from the receptor level to unmyelinated sensory nerves, which carry the information through a neuro-exchange center at the sacral spinal cord. At that point, it is converted to a motor response and carried back to the bladder muscle, which facilitates contraction and allows for bladder emptying. It is very basic.

The adult system is more complicated, at least in part because as humans, we must maintain social acceptability. Being socially acceptable demands pelvic dryness. Our pants cannot be wet – we must not be tied to bulky protective undergarments, the kidneys must be protected from hostile bladder filling pressure, and finally, voiding must be volitional.

Page 6

To accomplish all of these things, higher centers must be involved to coordinate bladder filling and emptying. This is done by using our Adult Neural Network for voiding.

As we alluded to previously, the Adult Neural Network for volitional voiding takes over after the long spinal tracts are myelinated. This usually occurs before the age of five years and the Infantile Neural Network, which operates via a simple sacral reflex arc, is suppressed. Essentially, it is rendered inactive. Now, the Adult Neural Network for voiding is preferentially selected, and because our long tracts have completed the process of myelination, we have the speed to transmit sensory signals to higher centers where they can be assessed and acted upon before any urine leakage from the bladder can occur. This process is fairly complex, but the following scenario is generally considered the sequence of events.

Firstly, it is important to remember that our lower urinary tract runs under a concept known as Inhibitory Control. This means that the vast majority of neural communication occurs via the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. Sympathetic communication at the level of the detrusor is mediated via a specific subtype of beta receptors, which are only found in the lower urinary tract (LUT), known as B3 receptors. This B3 receptor activity maintains the detrusor in a relaxed state to allow for bladder filling at increased volumes under low pressures. Simultaneously, sympathetic communication at the level of the proximal urethra and bladder neck occurs via alpha receptors (A1a) and keeps the IS and the ES in a contracted state so that continence (dryness) is maintained at socially acceptable levels.

Secondly, once bladder-filling information reaches a certain volume and tone, the information is translated from the receptor level to sensory nerves, which carry the information through a neuro-exchange center at the sacral spinal cord. Then, the information is relayed up to the pontine micturition center in the brainstem via myelinated spinal tracts at lightning speeds.

Page 7

At that point, that sensory information is sent to higher cerebral centers, where it is assessed. If it is deemed socially acceptable to void, a volitional somatic neuro-communication is generated, which relaxes the striated component of the ES. This voluntary neuromuscular relaxation is the trigger for the withdrawal of sympathetically mediated inhibitory control. Relief of sympathetically mediated inhibition means that B3 stimulation at the level of the detrusor is removed and the bladder becomes unstable and contractile. Simultaneously, withdrawal of sympathetically mediated inhibition at the level of the bladder neck means that the sphincteric complex goes into a relaxed state and decreases bladder outlet resistance to allow for bladder emptying. Finally, milliseconds after all of this happens, parasympathetically mediated stimulation via muscarinic receptors at the detrusor allows for coordinated bladder muscle contraction and physiologic voiding.

Finally, it is important to note that there is a reflex loop between external sphincter muscle tone and bladder muscle activity. Essentially, as the ES is tightened and pelvic floor muscle tone is elevated, B3 stimulation is increased, which subsequently decreases bladder muscle contraction and detrusor tone.

The Hypothesis

Our position is that bodily stress induced by a traumatic situation causes an increased adrenalin release and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Adrenalin, or epinephrine, is an important transmitter for the sympathetic nervous system. Consequently, the adrenalin release produces an involuntary rise in ES and pelvic floor muscle tone, which in turn inhibits bladder contraction, making it almost impossible to void. There is now anecdotal MRI data to suggest that after initiation of the bladder neck opening, the external sphincter is the last to open.

Page 8

III. What We’ve Learned about Self-Treatment of Shy Bladder

In the last decade or so, many people report success in treating their shy bladder, some of them with techniques they themselves have “invented.” I remember receiving one email from someone who basically said: “Thanks for writing the book; I applied the techniques in it, and basically cured myself.” Well, as I’m fond of saying, more power to this person. However, unfortunately, most of the time it’s not so simple.

Why is this? I think there are a number of reasons for this.

First, one has to have the knowledge of how to effectively treat this (or any other) phobia. Second, there is this motivation problem. I’ll never forget a client whom I treated for a number of weeks, and who made very good progress in his sessions. But then, when it came to practice in the field, so to speak, he would never do his “homework” from week to week. Hence, gains were not maintained week to week, and the treatment program basically stopped in less than six sessions.

This is similar regarding workshops and thus becomes the second reason. I tell people in attendance that for every one person at the workshop, there are at least 10 who thought of coming but became too afraid or anxious beforehand to actually commit. There is a reason we’ve dubbed this affliction “avoidant paruresis.”

Third, it is very hard to make significant changes in one’s life. Whether losing weight, stopping smoking, or getting into recovery from paruresis, it’s hard work. At workshops, I tell people that the Saturday session, when we are fluid loading and practicing all day, maybe one of the hardest days of the participant’s life.

Page 9

So, given these factors, it’s no surprise that most people do not successfully recover from paruresis on their own. That is why people usually seek individual treatment, come to a workshop, and/or attend a support group to facilitate their recovery.

That said, there are at least two methods of treating paruresis that have evolved over the last decade and do not require the usual form of treatment that many undertake.

The first is what we have come to refer to as the “breath-hold” technique. Championed by Dr. Monroe Weil (2001), this method is deceptive in its simplicity. Quite simply, all one needs to do is to breathe normally, and on one of the out-breaths, decide to exhale three-quarters of the way. That’s it. Plain and simple.

However, the trick is to hold your breath until you literally feel you might pass out. This seems to take, on the average, 30-60 seconds. And, as we’ve discovered, it seems that a lot of people simply can’t hold their breath long enough. At workshops, I’ve noticed that breath-hold seems to work for about 10-15% of those who try it for the first time.

For those who are successful, what appears to happen is that the pelvic floor literally “drops” or relaxes, and they “automatically” start peeing. There is no volition involved. Apparently, you have either created a situation where the CO2 builds up in the bloodstream and around the bladder neck (or whatever offending muscles), and the muscles involuntarily relax, and/or you have deprived the muscles of oxygen, and created the same effect.

There is much advice about how to do the “breath-hold” on the IPA website (http://paruresis.org/phpBB3/) and a number of demonstration videos on YouTube. We issue one caveat: please check with your medical doctor before engaging in breath-hold, especially if you have any heart problems.

Page 10

The other surefire technique that people have adopted for coping with paruresis is self-catheterization. While for many this sounds ghastly, in actuality, it’s not very hard, isn’t really painful, and in some cases, such as being trapped on an airplane for 12 hours or more, the only real option people have.

I always tell people to remember that a certain percentage of the population has to self-catheterize daily, namely, those who are paraplegic. In fact, their life depends on it. And, I don’t think they are particularly bothered by it, or get an undue amount of bladder infections. So, I tell people if you must urinate in certain situations, and aren’t sure you can (for example, not being sure that you could urinate in a plane bathroom sitting down), then learn how to self-cathe. Just ask yourself: would you rather be sitting in a plane with your bladder screaming in pain, or go to the bathroom and relieve both your bladder and the pain?

In this book, I won’t go into details about self-cathing. Again, there is a lot of information on the IPA website, as well as instructional videos online. However, a caveat here too: we highly recommend that instead of learning how to do it yourself, you make an appointment with a urologist or urologic nurse and learn how to self-cath properly. While it’s hit and miss finding a urologist who will teach you (it appears that urologists are squeamish about teaching apparently “able-bodied” people to self-cath, and may be concerned about liability issues), we know a number who are quite “paruretic-friendly” and are more than willing to do so. We usually recommend that you just call around your hometown to various urologist offices until you find one who is willing to help you. There is also now an article about paruresis on the main urology website (http://www.urologyhealth.org/urology/index.cfm?article=107), which should help convince some skeptical urologists that this is a legitimate condition.

For some, it simply is not practical to seek individual treatment, find a support group, or get to a workshop. And yet, s/he wants to get into recovery. What to do?

Page 11

Well, quite simply, you can practice on your own. By taking the steps listed in our first book, you can create a behavioral hierarchy (see Appendix I) and begin your own recovery. The trick is to create a hierarchy that is gradual, or step-by-step. The biggest mistake many make is to set up a hierarchy in which the first step is too difficult, hence leading to what we call a “misfire.” (We do not use the terms “failure” and “success” because they imply an evaluation of your performance.) Rather, you want a first step in which you are able to go. Thus, always err on the side of caution, since this is much easier than wasting time finding your “baseline” for being able to go.

Common places to start practicing include establishments with single, locked bathrooms, such as Starbucks or Whole Foods. For most, this provides enough safety to be able to go, unless, of course, the fear of someone waiting for you comes into play. Then, you have to find a single, locked bathroom with even more privacy.

After that, you can go to places like Office Depot, Staples, and Home Depot. Also, many supermarkets, drugstores, and hospitals now have good practice bathrooms. These generally fall into the category of what I call “semi-isolated” public bathrooms.

Finally, it’s off to a mall. What I advise people here is to start during the week in the anchor department store bathrooms in the mall, for example at a Macy’s or J.C. Penney’s, and then move on to the food court bathrooms before things get busy. The ultimate challenge, of course, is to practice at these food courts during the busy time, that is, Saturday or Sunday at lunchtime. I believe any self-motivated person can implement some variation of the plan I have just described, and have “success” in their paruresis recovery work. Of course, fine-tuning the practice may be necessary, and that is where the talk forum on the IPA website can be useful.

Page 12

Usually, if one puts up a post, someone(s) will respond with helpful suggestions of what you can do to improve your practice.

There are two important refinements to how people practice that I’ll mention here.

The first is the urgency level at which one practices. Usually, I tell people to fluid load with water until they have an urgency level of about seven on a 10-point scale, with one being low and 10 being high. This works for most people. However, two caveats:

Some people find it easier to begin practice a lower urgency levels, let’s say a three or a four. If you fall into this category, that is fine; adjust your level accordingly. There is no hard and fast rule that says you must practice at a seven-urgency level.

Also, realize that there is a practice sub-hierarchy of “not going.” That is, one can simply desensitize oneself to a feared situation with an urgency level of zero. This is particularly useful, for example, for people who never use public bathrooms. Thus, just going into a public bathroom can create high anxiety levels for some. So, first, simply practice walking into a bathroom and then walking out. Next, practice going into a bathroom and walking around for about 15 seconds. One can then progress to washing hands at the sink, combing your hair, and then eventually walking into a stall and staying there for various periods of time. Finally, you can progress to standing at a urinal for increasing intervals of time, again, with no urgency to go. Being able to do the latter for five minutes or more is usually a useful exercise for anyone with paruresis.

The last thing I want to discuss in this chapter is the power of “the secret.”

For many people with paruresis, a shy bladder is a secret you hide from others at all costs. I think this is a mistake, and moreover, actually perpetuates the “syndrome.”

Page 13

If nothing else, holding onto a secret, especially with people close to you, is an energy drain. Moreover, it often requires going to great lengths so people won’t discover your “secret.” We know of people who have been in relationships with significant others for 20 or 25 years and never told him or her (or anyone else, for that matter). We even know of marriages and close relationships that have ended due to the power of the “secret.”

At what psychic, emotional, and personal costs do you perpetuate such a secret? Usually, the cost is very high. I believe that it is much better to begin telling people around you, selectively at first, and then more broadly. In virtually all cases, the person(s) you tell will likely be sympathetic (the one exception could be certain workplace situations). Moreover, if someone you tell is not sympathetic, is that person truly a friend?

Part of the recovery process is letting go of this secret. And, the more people who know about this disorder, the more educated the general public becomes about shy bladder is a real problem with real impacts on people’s lives.

Page 14

IV. Latest Techniques for Treating Paruresis

One of the most useful concepts to develop in the last 10 years for understanding and treating shy bladder is the notion of the “ironic process” (Wegner, 1994). Essentially, the idea here is that the harder we try to overcome our problem, the more difficult it will be for us. The “Chinese finger trap” is used to illustrate this at workshops. People put their fingers in it, and then try to pull them out. The harder one struggles or pulls, the more difficult it is to release it. The way to get out of the finger trap is to counter-intuitively “push” your finger further into the trap, thus releasing its grip.

The analogy is obvious. The harder we struggle to overcome paruresis, the longer the battle. Like the baseball player who “chokes” on the throw from second to first base, or the golf player who develops the “yips” and can no longer make the easiest of putts, we “choke” at the bowl, so to speak.

So, to overcome the problem, one must actually fully accept the problem in the first place and stop struggling with “it.” This dovetails nicely with some of the newest forms of psychotherapy in the field, namely Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (see for example, Hayes, 2005) and Mindfulness Therapy (MT) (see for example, Germer et al., 2005). Drawing heavily from some of the ideas in Buddhism, the goal is not to “overcome” the problem, but in essence, to become one with it. Once you can do that, the struggle is over, and you can move forward.

This, of course, is easier said than done. In particular, for those with paruresis, it’s not just a psychological problem, but a biological one, too. The newest research

into brain/body problems shows that people are hardwired in many ways, and in the case of paruresis, the role of adrenaline and how it helps induce the problem is truly significant.

Page 15

For most of those seeking treatment for shy bladder, it is really the secondary paruresis that is at least half the problem. Consequently, while CBT is the primary form of treatment, ironically we are actually looking for perceptual changes to help “overcome” the problem.

I like to tell the story of one of our support group leaders who describes the recovery process well. When he first got into recovery, he was so tied up by this problem that he would have trouble peeing in a bathroom if he saw his own reflection in the mirror. As he progressed with his recovery, he noticed several things. Among them was a particular bathroom at a casino. He remembered that before treatment, his perception of the bathroom was of a “dangerous” place, with the urinals so close to the casino floor that he literally felt he could take his hand, put it around the corner, and pull the slot machine.

The next time he went into that bathroom, after much practicing, he was startled to see that his remembered “perception” of this bathroom was either wrong or it had been altered. The bathroom no longer seemed so threatening, and the slot machines were quite a distance away from the urinals. When he had first gone into this particular bathroom, he had been on such “hyper-alert” that his perceptions had been quite distorted.

I also like to relate my own recovery story at workshops having to do with the changing of perceptual fields. I had gone to the state fair in Maryland and got there not having thought or worried about how I was going to use the bathroom there (state fairs are notorious for the poor state of their public restrooms). Once I arrived and realized I had to use the bathroom, I headed for the first one. The line was out the door, and the men were standing shoulder to shoulder at the urinals. I waited in line, nonplussed, and even though I “knew” I wasn’t going to be able to go, I gave it the old college try. Sure enough, I “misfired.” However, I wasn’t fazed by this, and simply proceeded down the hall, passed the sheep, goats, and pigs, and found another, less crowded one. While the urinals were quite unattractive

Page 16

(low-bowl design, no partitions), there was an empty stall. I walked in, stood up, took a few seconds, emptied my bladder, and was done. Plain and simple. No worries and the rest of the day was enjoyable. A fundamental shift for me: no pre-anticipatory anxiety before going to the fair, and no obsessing once there about using the public restrooms.

The key here is that urination was “normalized.” The worry, anticipatory anxiety, and fear were no longer present. But, I hadn’t “struggled” to get to that point; it was as if I had an epiphany, and in the moment realized that paruresis was no longer an albatross around my neck. I was “free,” in a sense, from the problem. Importantly, this didn’t mean I could pee in all situations; what it meant was that I went with the flow, so to speak, adjusted to the situation, and solved the problem without worry.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy implies just that: cognitions and behaviors. My experience in terms of treating people with paruresis is that while the road to recovery requires a fundamental shift in cognitions and perceptions, it is pretty fruitless to try and address those directly. There are differing points of view on this, but I find that changes in the cognitive/perceptual field follow changes in behavior, and not necessarily vice-versa, at least for this problem. If we view our obsessive worry and thoughts about paruresis as unhelpful “epiphenomena,” or as I am fond of saying, simply “garbage” thoughts, and not get caught up in them, we can get to the business of treating our condition.

Anxiety is the major culprit we are fighting. When our anxiety levels are above a certain level (let’s just say five on an arbitrary, subjective 10-point scale), we are going to have more difficulty peeing. Our nervous system gets activated, affecting both our bladders and our brains. Once we get above a certain level, let’s say a seven, we will be unable to pee in almost all public situations. The combination of the adrenaline rush and the obsessive, repetitive and unhelpful

Page 17

thoughts in our heads are a surefire sign that we will not be able to get the job done. Thus, the key is to reduce anxiety levels into the range in which we’ll be able to urinate.

Another way of looking at our problem is that there is a “short-circuit” in our system, and consequently, the electricity (or in our case, urine) stops. There is no power because the circuitry is “broken.” In our case, however, a “repair” is not a simple soldering job. We cannot fix the circuit in this way. Instead, we must go around the problem area, and actually build new pathways to get around the break. I like to see repetitive exposure therapy as the process of building that new circuitry. After numerous “successful” repeats, the new circuits are actually laid down, and we can pee again.

There are going to be new therapies and refinements to the old ones that over time will make the work we do more and more effective. Perhaps some adjunct medications will help in the process, too. However, nothing will substitute for beginning the recovery process and sticking with it, modifying things along the way. Whether in one year or in ten years, most people who stick with the plan/program will eventually reach the point where paruresis no longer has a hold over their lives, and they can proceed in life living with this“ minor” disability or inconvenience. But it will no longer be a show-stopper.

One last thought. I like to use the analogy of the stock market at workshops. Progress in the short term can be up, sometimes dramatically so. However, there are bound to be blips and downturns along the way. Usually, these are minor aberrations. That is two steps forward, one step back. There is the occasional deep downturn (one step forward, two steps back). Over time, though, historical data supports the point that the stock market is one of the best long-term investments for your money. The same is true for continuous practice in overcoming or recovering from paruresis.

Page 18

V. Workshops and Support Groups

By now, the International Paruresis Association, through the Shy Bladder Center (SBC), has conducted over 150 workshops across the globe. Over 1100 unique individuals have participated (a number of people attended more than one). Workshops have been conducted in seven different countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Russia, the U.K., and the U.S.) in over 40 different cities. Data from workshops conducted from 1997 through 2003 is summarized in Appendix B, but in brief, the results have been excellent. I have also written a description of the group process involved in our workshops (Soifer, 2013).

Some of the interesting observations I have made over the years (I have presented well over 100 workshops myself) follow. Many more men than women attend (roughly a 9:1 ratio). The similarities across cultures are amazing. A common theme among participants concerning the origins of their paruresis is some sort of bullying experience in childhood or adolescence, often in school.

The workshops are a transformational experience for many, and a lot of people realize significant progress over the course of the weekend.

I am constantly amazed at the dynamics at workshops, and how healing they are for many participants. Some, who have never told a soul in their lives, now openly bare one of the most painful secrets they have been carrying around, often since childhood. The instant rapport most feel the first night when sharing stories is wonderful to see. I never get tired of listening to people tell me how paruresis has affected their lives. I often wish a TV crew was there to record how this little “secret” phobia has so impacted people with paruresis and the loved ones around them.

After a workshop, people are often on a high and go home to the same environment that they had left. It is not unexpected for them to feel a letdown after the weekend experience. I tell everyone before the workshop ends that the key to ongoing recovery is “practice, practice, practice.” Not everyone listens to me.

Page 19

I inform people that based on my experience over the years, people need to practice a minimum of once a week (ideally, every other day) to maintain the progress they made at the workshop. While people can do this by themselves, it is much easier to do with the help of a support group. Currently, IPA has support groups in 11 different countries and exactly half (25) of the U.S. states. Not all of them, unfortunately, are very active.

For those who have a support group near them, I tell them to join it. For those who don’t, I encourage them to start one. We have a support group manual we share with leaders, and there are two International Support Group leaders: one for men, and one for women. It isn’t hard to start one – basically, one makes a commitment to set, at minimum, a monthly meeting time, at the same place (usually a mall) and same time (weekends are good), and then to show up. At the very least, it gets that one person to practice once a month.

I’ve noticed over the years that those who make a commitment to run a group often seem to recover more quickly and have better results maintaining their gains than the average person in recovery. Clearly, just the commitment to show up and practice regularly probably makes all the difference in the world.

We also have a “pee-buddy” system: on our website, people post looking for practice buddies across the country. We have no way of knowing how well this works, but anecdotally, people have told us that they have found practice partners this way. Of course, people can do this through support groups, or simply enlist friends or family members to help them. I once had the idea of even having people wear yellow armbands in restrooms to let others know they had shy bladders and could use some help; the idea didn’t go over too well.

IPA will also soon be setting up a phone buddy system, where people who want to talk to someone who is in recovery from a shy bladder can do so. This phone support system will be the latest way in which the organization hopes to help people with this difficulty.

Page 20

It is hard for isolated people in a particular city, region, or country to find support for this problem. The best way now is through our moderated talk forum; several exist in other countries, too. Ideally, people will eventually hook up with others afflicted with paruresis, and at least have a buddy to work with. Sometimes, support groups form this way. Whenever a minimum number of people commit to a certain area (usually five to seven), the IPA is committed to making a workshop happen there.

For a variety of reasons, the work environment is still one of the hardest places for people to deal with and make progress on their paruresis. Obviously, the work environment poses unique challenges for people, and some feel (and perhaps rightly so) that their jobs can be or are jeopardized by the situation. Ideally, as people practice more and more, their recovery should eventually generalize to work. However, this isn’t always so.

If one doesn’t have the luxury of enlisting a “pee-buddy” at work, and the situation is a difficult one, I have various ways of helping people practice in those situations. They vary so much that it is hard to provide any practical advice here. However, I will say that in certain situations, one needs to ask for reasonable accommodation in the workplace, and while this doesn’t mean a private bathroom all to yourself, it does mean flexibility on the part of the employer. More on this will be covered in the next chapter on the law and paruresis, and what someone’s rights are in such a situation. I will say that being proactive and assertive here is important. This is not to be construed as medical advice, nor for that matter is anything else I’ve said in this E-book.

If you have time, you should practice first on trains, buses, or some other moving vehicle (e.g. an RV). You must treat this as just another hierarchy in your recovery (though a special one), starting with the least difficult (e.g. going on a train that is not moving) to the most (going on a bus standing up, from my experience).

Page 21

Airplane work is a tricky business. I don’t need to tell you this. Not only are you “trapped,” but motion and other factors (very small toilets, for example) make it difficult for many people to go (how many people do you see using airplane bathrooms?!)

There are three basic strategies: 1) learn to cath; 2) suppress the production of urine, and therefore urge to go (desmopressin, antihistamines, and/or ibuprofen), and 3) learn how to go. It is the latter I’ll deal with here.

First – if at all possible, break up your trip into several or more segments of no more than four to five hours. This will make it less likely you’ll get stuck on board with a full bladder. Second, practice, if at all possible, on short flights between where you live and somewhere about one-and-a-half to two hours away before any major trip – business or personal. A buddy would be helpful, but not necessary. I have done this with one person so far from Baltimore to Atlanta.

Third, try and take a plane that has a more conducive bathroom situation (e.g. avoid Southwest with its two bathrooms in front and back). Try, I think, to take an airplane with bathrooms in the middle and back, especially for practice. The website http://www.seatguru.com/ can help. Jumbo jets are best for international flights, or for the first leg of what will be an overseas flight.

Lastly, and perhaps most controversial and potentially most exciting – several members have reported success with valium, at least one in combination with urecholine (bethanechol chloride). You must talk to a doctor about the combination and dosage for you. For some, these medications are not a good idea.

Page 22

VI. Paruresis, Drug Testing, and the ADAAA

Almost since the inception of the IPA, we have been fighting for alternatives to urine drug testing (meaning saliva, hair, blood, and the patch). As of this writing, I believe that we are very close to this goal, in that oral fluid drug testing will be approved as an alternative by the Substance Abuse Mental Health and Services Administration (SAMHSA) in the relatively near future (check http://nac.samhsa.gov/DTAB/index.aspx for updates).

In September 2008, George W. Bush, like his father before him, signed a major piece of federal legislation in the disabilities arena. Known as the Americans with Disabilities Act As Amended (ADAAA), it greatly expanded the definition of a disability. The reason the act was needed is that the Supreme Court, in the years prior to the act, had greatly narrowed the definition of disabilities.

One of the additions in the ADAAA is that it clearly states that bodily functions related to the bladder are covered under the act. On the surface, it would seem to imply that paruresis or shy bladder would be considered a disability.

There have been no major court cases to clearly rule on this issue. (IPA has done extensive research of legal cases concerning paruresis.) However, since most of the drug testing issues we deal with are work-related (the exception is prison), they fall under the purview of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC has issued extensive rules concerning the ADAAA and how they do or don’t apply to work situations but had not addressed shy bladder in those regulations.

The IPA took the opportunity to write the EEOC about shy bladder, asking it specifically whether shy bladder would be considered a disability. While the EEOC could not issue an actual decision, it did issue (after extensive “lobbying” on our part, which included asking various U.S. Senators to request the letter from the Commission) what is called an “informal opinion” on the issue. The following is the full text of that letter:

Page 23

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

EEOC Office of Legal Counsel staff members wrote the following informal discussion letter in response to an inquiry from a member of the public. This letter is intended to provide an informal discussion of the noted issue and does not constitute an official opinion of the Commission.

ADA: DEFINITION OF DISABILITY UNDER ADAAA

August 12, 2011

[ADDRESS]

Dear ____:

This is in response to your June 1, 2011 letter to General Counsel P. David Lopez asked whether paruresis is a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), as amended by the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (ADAAA), and under the regulations implementing the ADAAA published by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) on March 25, 2011.

According to the literature you provided, paruresis (sometimes called “shy bladder syndrome” or “bashful bladder syndrome”) is the inability to urinate in public restrooms or in close proximity to other people, or the fear of being unable to do so. Paruresis is generally considered to be an anxiety disorder and typically is treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Your letter states that paruresis is also a chronic pelvic floor dysfunction. Individuals with paruresis sometimes are subjected to adverse employment actions because they are unable to pass standard tests designed to detect the illegal use of drugs, and are denied permission to take alternative tests that do not involve urination.

As was true prior to the ADAAA, the determination of whether someone has a disability requires an individualized assessment. The ADA defines “disability” as:

- a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities (sometimes referred to in the regulations as an “actual disability”); or

- a record of a physical or mental impairment that substantially limited a major life activity (“record of”); or

- when a covered entity takes an action prohibited by the ADA because of an actual or perceived impairment that is not both transitory and minor (“regarded as”).

42 U.S.C. § 12102(1); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(g)(1). To be entitled to reasonable accommodation, such as being given the option to take alternative drug tests, an individual’s impairment must meet the first or second definition above; individuals whose impairment only meets the third definition are not legally entitled to accommodation. 42 U.S.C. § 12201(h); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.9(e).

Although the amended regulations and accompanying interpretive guidance (appendix) provide illustrative examples, those are by no means the only impairments that are considered disabilities. On the contrary, many impairments that are not specifically mentioned, including paruresis, will be disabilities if they meet any one of the three definitions above. Moreover, as a result of the ADAAA and the EEOC’s implementing regulations, it is now far easier than it previously was for individuals to demonstrate that they meet one of the definitions of “disability,” for reasons discussed below.

I. Coverage Under the First or Second Definition of “Disability”

A. Major Life Activities Now Include Major Bodily Functions

Page 24

Under the ADAAA and the EEOC’s regulations, an individual with paruresis has a disability under the first or second definition if his or her condition substantially limits (or substantially limited in the past), one or more major life activities. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(1)(A), (B); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(g)(1)(i), (ii). As a result of the ADAAA, major life activities include major bodily functions, such as bladder and brain functions, and functions of the neurological and genitourinary systems. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(2)(B); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(i)(1)(ii). Major life activities also include activities that the EEOC and many courts recognized as major life activities prior to the ADAAA, such as caring for oneself. See 42 U.S.C. § 12102(2)(A); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(i)(1)(i).

B. “Substantially Limits” Is Not Meant to be a Demanding Standard

Both the statute and the amended regulations state that the term “substantially limits” shall be construed broadly in favor of expansive coverage. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(4)(A); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(j)(1)(i). The term now requires a lower degree of functional limitation than was required prior to the ADAAA; an impairment does not need to prevent or severely or significantly restrict a major life activity to be considered “substantially limiting.” ADA Amendments Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-325, § 2(b)(4), (6), 122 Stat. 3553 (2008); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(j)(1)(ii), (iv)–(v).

In addition, the determination of whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity must be made without regard to the ameliorative effects of mitigating measures (with the exception of “ordinary eyeglasses or contact lenses”). 42 U.S.C. § 12102(4)(E); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(j)(1)(vi). Thus, an individual’s paruresis substantially limits a major life activity if it would do so in the absence of treatment, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication.

The statute and regulations also state that an impairment that is episodic or in remission is a disability if it would substantially limit a major life activity when active. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(4)(D); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(j)(1)(vii). Therefore, the determination of whether an individual’s paruresis substantially limits a major life activity is based on the limitations imposed by the condition when its symptoms are present (disregarding any mitigating measures that might limit or eliminate the symptoms).

II. The Statute and Regulations Make it Easier for Individuals to Establish Coverage Under the “Regarded As” Definition of “Disability”

Under the ADAAA and the EEOC’s regulations, a covered entity “regards” an individual as having a disability if it takes an action prohibited by the ADA (e.g., failure to hire, termination, or demotion) based on an individual’s impairment, or on an impairment that the covered entity believes the individual has unless the impairment is both transitory (lasting or expected to last for six months or less) and minor. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(3); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(l). Under the ADAAA, the focus for establishing coverage is on how a person has been treated because of an impairment (that is not transitory and minor), rather than on what an employer may have believed about the nature of the impairment. 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(j)(1)(iii). Paruresis does not appear to be a transitory impairment. Therefore, if a covered entity terminates, fails to hire, or takes a similar adverse action against an individual because of paruresis, whether the condition is real or perceived, the individual probably will be “regarded as” having a disability.1

However, as noted above, an individual who is covered only under the “regarded as” definition of “disability” is not entitled to a reasonable accommodation. 29 C.F.R. § 1630.9(e). Thus, someone who needs a reasonable accommodation for paruresis (e.g., to be permitted to take a hair, saliva, or patch test intended to detect the illegal use of drugs rather than a urine test) would need to demonstrate that his or her paruresis constitutes either an actual or record of disability. In addition, an employer determining if it must grant a request to take an alternative drug test will be able to consider whether such a test would cause an “undue hardship,” which may include whether an alternative test is an effective means of determining the current illegal use of drugs.

III. Conclusion

As was true prior to the ADAAA, a person with paruresis is required to show individually that he or she meets the definition of “disability.” The ADAAA and its implementing regulations make this showing much easier,

Page 24

by including bladder and brain functions as major life activities, lowering the standard for establishing that an impairment “substantially limits” a major life activity, and focusing the determination of whether an individual is “regarded as” having a disability on how the individual has been treated because of an impairment, rather than on what the employer may have believed about impairment. No negative inference should be drawn from the fact that paruresis is not specifically mentioned in the EEOC’s regulations implementing the ADAAA.

We hope this information is helpful. This letter is an informal discussion of the issues you raised and should not be considered an official opinion of the EEOC.

Sincerely,

/s/

Peggy R. Mastroianni

Legal Counsel

Footnotes

1 The question of whether someone with paruresis is regarded as having a disability is separate from the question of whether an employer’s action is lawful. For example, an employer may exclude someone from a job because of an impairment if the impairment renders the individual unable to perform a job’s essential functions or if the impairment poses a direct threat (i.e., a significant risk of substantial harm) to the individual or others in the workplace.

While this is not a legal opinion, we read the letter as basically saying that given the right circumstances, paruresis would be considered a disability. The extensive blogging by lawyers in the disability field, both for and against our position, would seem to indicate we probably have the right interpretation. However, and this is really important until there is a legal case to this effect, we can only guess how the courts would rule. I have advised people with paruresis, if need be, to show this letter to their Human Resource department at work if s/he is confronted with a drug testing situation and an alternative to urine testing is not offered after a request is made for one.

Probably in part due to this letter, the Drug Testing Advisory Board (DTAB), which is part of SAMHSA, has finally moved on to the question of providing a legitimate and recognized alternative to urine drug testing in the form of oral fluids, specifically saliva. What we know at this point is that DTAB has sent proposed oral testing guidelines for federal approval, and it is

Page 25

our understanding is that these new rules are to be published at some point in the future in the Federal Register.

While this is very good news, and hopefully will ultimately be what we have been requesting from the Federal Government for over a decade, there are a number of very important unanswered issues and questions. The two that occur to me are: 1) how long will it take the private industry to follow the Federal Government, and 2) will employers, on a volunteer basis, provide this form of alternative testing when requested by someone with paruresis?

Regarding the first question, the long-term prognosis is good. I say this because several Fortune 500 companies, such as Georgia Pacific, already do oral fluid testing of their employees, and have done so for a number of years. A number of smaller, private companies do likewise, but they are certainly in the minority. I would imagine that within five to 10 years, for a variety of reasons (some obvious, some not), saliva testing will become the norm in the corporate world.

The second question, I think, is less clear. One would like to think that it will be the employees’ choice of which test they would want to take, but it could be otherwise. So, this may be another battle we will have to fight. That too could take five to 10 years to establish as the norm.

Finally, I think it is important to acknowledge that for people in prison and the military, the choice of oral fluid testing will probably not be an immediate option. But, I think over time, it too will be widely available in addition to, if not ultimately replace, urine drug testing.

Page 26

VII. The Future of IPA and for People with Paruresis

Since IPA’s founding in 1996, a lot has changed for people with paruresis, but unfortunately, a number of things have remained pretty much the same.

To begin with, and perhaps most importantly, many more people know about and/or are seeking treatment for shy bladder. Just from our organization’s perspective, we can say that thousands of people have sought treatment through our workshops and the Shy Bladder Center’s (http://www.paruresis.org/sbc_therapists.html) therapeutic network. The discussion forum on the IPA website has almost 8,000 registered users, and there have been tens of thousands of posts there since it started. There has been quite a bit of research in the area of paruresis (see Appendix B). We have had hundreds of articles in newspapers around the world, and I have done many radio and TV interviews, too. The organization is actively engaged in social media activities now, as well.

IPA is moving into its 16th year now, stronger than ever. For our 15th anniversary, we produced a PowerPoint presentation of all our accomplishments to date, which is available at http://paruresis.org/IPA15YearsFinalDraft.pdf. Our most significant accomplishment, other than helping thousands of people recover or get into recovery from paruresis, is the progress we have made on alternatives to urine drug testing in the workplace. A close second, in my estimation, would be in our understanding of the mechanism behind paruresis.

Even still, the organization has so much more to do. I am fond of saying that the need for IPA will certainly go beyond my lifetime. Most significantly, virtually nothing has changed in the environment that causes and sustains paruresis, namely school bullying and the design of public restrooms. Tackling the former issue will require a major campaign to make people aware of how school bullying contributes to causing shy bladder, and making headway on the latter issue will require an active American Restroom Association (www.americanrestroom.org).

Page 27

Secondarily, there is the task of educating the mental health and health communities about paruresis. Over the last decade and a half, I believe significant inroads have been made in the education and training of some in the mental health community about shy bladder. There is a network of therapists through the Shy Bladder Center in particular who can effectively treat the disorder and other therapists either practicing in Anxiety Disorder Clinics or in private practice throughout the U.S. who can help people with paruresis. However, a client must do their homework to find them (note: buyer beware!). In particular, there has been a growing presence of “charlatans” advertising on the web their “miracle” cures for paruresis. As far as I know, virtually no one has experienced such a “miracle” in their life.

Much still must be done to educate the health community in general about this disorder. In particular, the medical community still knows little about our problem. Urologists, who should know the most about our disorder, with few exceptions, still appear to be in the “dark ages” when it comes to paruresis. The exceptions here are a few far-thinking urologists, neurologists, and urologic nurses. General medical practitioners, unless she has been self-educated about paruresis or have learned about the disorder from a patient, know as much or as little about the problem as the general population.

Thus, a major educational campaign targeting the American Medical Association (AMA) must be undertaken. Along these lines, work needs to be done to get our issue before the National Institutes of Health and Mental Health (NIH, NIMH). In particular, we are beginning the work, modeled along the lines of what the National Vulvodynia Association (NVA) (http://www.nva.org/) has done, to get the U.S. Congress to direct the NIH and/or the NIMH to take our disorder seriously. Regarding the understanding of why we have paruresis, our next step, other than what I just mentioned above, is to fund primary research to unravel its mechanism. Now that we

Page 28

understand the basic outlines of why we have this disorder, funding researchers to delve deeper is essential. Organizational models for this are again the NVA and the Selective Mutism Center (http://www.selectivemutismcenter.org/Home/Home). Interestingly, there are some similarities between those disorders and ours. With vulvodynia, we have another chronic pelvic floor problem, and with selective mutism, we have some survey data that indicates about half of the selectively mute children have paruresis.

In order to ensure the long-term viability and sustainability of the IPA, the organization’s Board of Directors has recently launched an endowment campaign. The goal is to raise $1 million by 2021 (IPA’s 25th anniversary) to permanently fund the organization. By providing enough money yearly to allow the IPA to basically staff the office, there will no longer be the worry, that plagued the organization in its early years, that it might not survive until the next year. One can read more about the campaign at (https://app.e2ma.net/app/view:CampaignPublic/id:1408294.11080311561/rid:9a9ff94aed556a0efc50571e39531ee5).

I cannot rightly convey in words what being part of this worldwide “movement” has meant to me. Other than my personal recovery (and those who know me know that I don’t mean “cured,” but that I now live my life free of any worry concerning paruresis), I have been blessed to be able to help so many people get into recovery from this affliction. Between my clients and those attending IPA workshops, I have met so many interesting, creative, intelligent, and well-functioning (other than paruresis) people. While we may still not have reached the “tipping point” for shy bladder, I feel we are close. When anyone can talk about their problem as freely as women today talk about breast cancer or men talk about prostate cancer, we will know we are there. While this may not change people’s individual suffering, at least those who have shy bladder will know that they are not alone.

Page 29

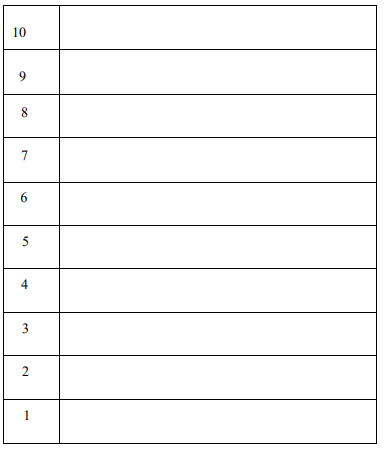

Appendix A: Desensitization Hierarchy Worksheet

Use this table to write down your own hierarchy. You should start at one (a situation where you can perform comfortably) and progress, in realistic and small steps, up to ten. Note: This will be one of several hierarchies needed to reach your eventual target.

Page 30

Appendix B: Updated Literature Review – Peer-Reviewed Articles

The last decade has seen a proliferation of peer-reviewed journal articles, dissertations, and books about paruresis (and in one case, parcopresis, or shy bowel syndrome). I will give a brief overview here. I expect that research will continue to expand in this area over time.

While the literature review in our book Shy Bladder Syndrome was meant to be comprehensive, at least one dissertation on the subject was missed. Antonio (1990) wrote about incarcerated prisoners, comparing in vivo exposure with cognitive restructuring as a method of treatment for paruresis, or as he called it back then, “psychogenic urination retention.”

Elitzur (2000) wrote the first Israeli article on paruresis. He took an eclectic approach to the treatment of three male patients in six sessions. He used a variety of methods, including relaxation, guided imagery, paradox, gestalt, metaphor, psychodynamic, and CBT. The two youngest patients (ages 18 and 25) reported complete recovery, while a 50-year-old man reported partial recovery. There was no long-term follow-up.

Soifer and Ziprin (2000) presented information to cognitive-behavioral therapists about paruresis in one of the main magazines for these practitioners. This started a trend of trying to educate mental health practitioners about this social anxiety disorder. Also that year, Watson and Freeland (2000) wrote about using “respondent conditioning” to treat shy bladder. In this successful case study of a woman, the team was able to help her more freely urinate when other people were around and help her go more quickly, too. Unfortunately, there was no follow-up to see if she maintained progress.

Page 31

Partially in response to Soifer and Ziprin (2000), Weil (2001) wrote of using what we call the “breath-holding technique” to help people with paruresis. Interestingly, Weil’s technique was based on the work of Wolpe (1969), who used carbon dioxide (CO2) to bring about a relaxed state in patients. While the amount of time necessary for the patient to hold their breath varied, somewhere between 10 and 45 seconds seemed to work. This treatment was successful for three out of three males.

Vythilingum, Stein, and Soifer (2002) did a survey of people with paruresis to see if it was a form of social anxiety disorder. This was the first study done using self-selected “members” of the International Paruresis Association (IPA). Thus, while the sample was limited, it did get information from 63 people (59 males, 4 females) for the first time. Using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), data showed that about half the sample was significantly impacted by the disorder. An association was found between paruresis and other mental health issues, in particular social anxiety disorder, depression, and other performance issues. On the other hand, it is important to note that it appears that 50% of those surveyed had no other symptoms associated with the paruresis.

Rogers (2003) reports on using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with a man who also suffered from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Since BPF is common in many males over 50, this is an important case study. The results showed that CBT was an effective treatment even when this medical condition was involved and complicated the paruresis.

Hammelstein (2003) wrote a general piece on paruresis for a German psychology journal. Hammelstein and Soifer (2006) wrote a provocative piece questioning whether the disorder was really a social phobia.

Page 32

In this article, the authors looked at a sample size of 226 Germans, of which 82 were women. Despite the limitations of the sample, what emerges is very interesting. It appears that those with social phobia and those suffering from paruresis have different characteristics. Most importantly, 75% of people who have paruresis did not meet the criteria for having social anxiety disorder (SAD) (and vice-versa: 75% of those with SAD did not have paruresis). Thus, on the surface, paruresis and social phobia seem distinct, questioning whether paruresis is really a sub-type of this disorder. While paruresis may best be described, based on this study, as a “functional disorder of micturition,” it is probably more likely that there are different types of paruresis, ranging from those who could be categorized as “social phobic,” and those who have more of a urological disorder.

Boschen (2008) wrote a brilliant article that truly expanded the repertoire and model for treating paruresis through CBT. In it, he presents a “revised cognitive and behavioral model” for understanding shy bladder that was taken from a recent understanding of other anxiety disorders. This leads to specific techniques for treating the condition.

The major contribution Boschen makes is to add more of the cognitive back into the CBT understanding and treatment of paruresis. The “micturition double-bind” is particularly interesting; either “failure” or “success” at the public toilet brings increased attention to oneself. Also, “micturition self-efficacy” thoughts, that is, how one expects to do a public toilet, can affect one’s performance anxiety levels before the act. Boschen then puts this all together and presents an illuminating “visual formulation model” for understanding shy bladder, one worth studying.

Soifer et al. (2009) examine the urologic literature, concluding that up to 36 different urologically identified disorders could be synonymous with paruresis. The most popularly identified terms in the

Page 33

urologic literature were “psychogenic urinary retention” and “non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder.” Amazingly, the terms paruresis or shy bladder are never used in this literature. The authors recommend that a consistent term be used in describing this disorder.

Soifer, Himle, and Walsh (2010) present the results of the use of graduated exposure therapy with over 100 clients who attended weekend workshops sponsored by the Shy Bladder Center of the International Paruresis Association. The results were encouraging: there was substantial improvement for many participants in their shy bladder symptoms post-treatment and at a one-year follow-up. However, as has been noted many times before, this was not a controlled study, and until one is done, we only have suggestive evidence of the treatment efficacy of using CBT for this disorder.

Abrefa-Gyan, Barrett, and Soifer (2012) wrote an article about how the Internet allowed an organization like the International Paruresis Association to grow and flourish. The organizational development of IPA is linked to different stages of advancement and growth in this era of the “computer revolution.” In particular, it is noted that people from across the globe suffering from the “secret phobia” of paruresis were able to anonymously connect online in a way that would never before have been possible.

Deacon et al. (2012) have made a significant contribution to the field of paruresis research by developing a much-needed valid Shy Bladder Scale. The 19-item scale could become a standard in the field for determining if someone is truly suffering from paruresis. The scale was highly internally consistent, and accurately assessed the person’s difficulty in urinating publicly, their levels of anxiety, and their degree of negative self-evaluation.

Page 34

Appendix C: Books on Paruresis

The first actual manuscript on the subject of shy bladder was published by McCullough (2000). Free to Pee was a groundbreaking treatise on paruresis, and did two major things. First, McCullough for the first time made the distinction between primary and secondary paruresis, which we illuminate in this manuscript text. Second, while he also takes a somewhat cognitive-behavioral approach to treating this disorder, he is the only author that I know of who throws in a hint of existential therapy into understanding this disorder and also brings in a bit of gestalt therapy to boot. For some, this approach is quite helpful. It is a tragedy that Dr. McCullough’s life was cut short by pancreatic cancer in the mid-2000s.

When Soifer et al. (2001) wrote Shy Bladder Syndrome: Your Step-by-Step Guide to Overcoming Paruresis, it was the first book on the subject of paruresis or shy bladder syndrome. We assume most of the readers of this update to that book are familiar with it, so we will not summarize it here. Suffice it to say that it was a groundbreaking work, bringing wide attention to this social phobia for the first time.

Herrmann (2003) wrote the first “playful” manuscript on the subject and titled it Bianca and the Bashful Bladder (Paruresis Comes Out of the Water Closet. This delightful little treatise looks like a children’s book but really isn’t. It’s the perfect gift for someone who knows nothing about paruresis, introducing the subject in a light and understandable way.

Typaldos (2004) did people with paruresis a real service by collecting a series of recovery stories in an edited work called “The Secret Phobia: Stories from the Private Lives of paruretics, written by people with “Shy Bladder Syndrome.” There are fifteen different stories in the manuscript, including mine.

Page 35

Just about every recovery technique is covered, and there is even one “I’m Cured!” story. A must-read for those wanting to know how others not only cope with this social phobia but lead relatively normal lives with it.

Kinneary (2005) wrote the book The Good Lord Hates a Coward: An Account of Life as a Merchant Seaman. Everyone owes Dr. Kinneary a debt, as he was the first person who really legally challenged in court his firing as the captain of a tugboat in New York City due to his paruresis. While winning a $250,000 judgment in a jury trial, Dr. Kinneary’s case was overturned by the New York State appeals court on a technicality. While an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was possible, the odds of it being heard were so small and the cost was so great that he and the IPA decided not to do so.

His book describes his ordeal with first the Coast Guard and the City of New York, and then the legal system in pursuit of justice. Interestingly, Dr. Kinneary is also “Joseph K.”, whom many will recognize as the main character in one of Kafka’s novels. Kinneary’s experience with the bureaucracy and the legal system was so “Kafkaesque” that it could make the hair on one’s spine stand up. Thank you, Joe.

Hammelstein (2005) wrote the first foreign language (German) book on paruresis that I know of, entitled Lass es laufen!: Ein Leitfaden zur Uberwindung der Paruresis. Roughly, this can be translated into English as “Let it Flow: A guide to overcoming paruresis.” Dr. Hammelstein and I have collaborated on several writing projects and did the first German workshop together, so it was my pleasure to see him write this book. Unfortunately, not speaking German, I cannot comment on the content, other than to say that it is a basic introduction for Germans to the problem of shy bladder syndrome.

Most recently, Olmert (2008) has written Bathrooms Make Me Nervous: A Guidebook for Women with Urination Anxiety (Shy Bladder). Ms. Olmert was a longtime IPA board member, and currently sits on

Page 36

its advisory board, and helps co-lead shy bladder workshops for women. Her book is an excellent guide to overcoming paruresis for women, but it can also be useful for men. Nicely illustrated with many helpful tidbits of information, it is the latest in a growing book of literature on the subject.

Finally, an honorable mention must go to Chalabi (2008), who, with my encouragement, wrote the first book on Shy Bowel Syndrome, entitled Shit Doesn’t Happen: Lifting the lid on Shy Bowel. We know very little about this phenomenon, and Baz Chalabi has pioneered the way with this book and a website (http://www.shybowel.com/). Also known as “paraparesis” (a term coined by Professor Alex Gardner of the U.K., also an IPA advisory board member), this social anxiety disorder is even less known and researched than paruresis. We are awaiting the emergence of a “Dr. Poop” to champion the cause of people with this bowel affliction. (I am affectionately known as “Dr. Pee” in some circles.) Mr. Chalabi has helped pave the way.

Page 37

Appendix D: Epidemiology of Paruresis

We owe a debt of gratitude to Liebowitz (1987), who in his now classic “Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale” asked the question, “Do you have a fear of urinating in a public bathroom?” This helped raise attention, even back then, to the phenomena of paruresis.

When Kessler, Stein & Berglund (1997) published their analysis of social phobia subtypes in a national sample, as far as I know, it was the first statistically meaningful data of paruresis ever published. Of course, we outline in our book other earlier studies of prevalence rates, but Kessler et al.’s 6.7 percent of the population became our litmus test for saying that about 17 million people in the U.S. (at that time) had paruresis.

We were well aware that the question in Kessler et al.’s survey was open to interpretation, because they asked, “Do you have trouble urinating in toilets away from home?” Thus, people with germ phobias, for example, could be included here.

Then, Stein, Torgrud, and Walker (2000) found that over 9% of a limited sample of Canadians had a fear of “using [the] toilet away from home.” In the first non-North American sample, a dissertation by Furmark (2000) found a prevalence rate for paruresis in Sweden to be over 11% of the Swedish population. In another international study, Hammelstein et al. (2005) examined paruresis in Germany and determined the “point prevalence” of this disorder. Based on a sample of 105 and using the Paruresis Checklist (PCL), they came up with a prevalence rate of 2.8%.

Ruscio et al. (2008), in a National Comorbidity Study – Replication (NCS-R) of almost 10,000 people between 2001 and 2003, found that 5.7 percent of the U.S. population feared using the public bathroom. Then, Green et al. (2011), in a National Comorbidity Study – Replication Adolescent (NCS

Page 38

-A), based on questioning over 10,000 youth ages 13-17 between 2001 and 2004, found that 10.3 percent feared using the public bathroom – almost twice the rate among the general population. Finally, the first well-done international study of social anxiety disorders in developed and developing nations (9 of the former, 11 of the latter), found a prevalence of 3.1 percent in developed and 3.2 percent in developing countries regarding fear of using a public restroom.

The overall sample size in this study was over 100,000 people, fairly evenly divided among the two types of countries. Thus, doing some very basic math, I realized that the world population has just reached 7 billion people as of this writing, approximately 220,500,000 people suffer from paruresis or shy bladder syndrome worldwide. To put this in perspective, this social anxiety disorder is about 10 times more prevalent than schizophrenia, and about as prevalent as depression around the world. This is not meant to say that one “disease” is better or worse than another; it’s just meant to show how relatively common shy bladder is, and yet not nearly as well known.

I think it’s most helpful to think about shy bladder syndrome or paruresis more like a continuum or spectrum disorder like autism (which, by the way, also affects far fewer people per capita). Thus, while a lot of people may occasionally suffer difficulty using a public restroom (dare I say about half the population or more?!), the number of people who suffer from shy bladder to the point that it constitutes an actual social phobia (that is, significantly interfering with one’s life functioning) is far less – maybe 10 percent of the reported prevalence rate (this is really a pure guess – and just meant to show the range of variability within this social anxiety disorder). Still, if even 1-2 million people (as an example) suffer from paruresis to this extent in the U.S. alone, it would put Shy Bladder on even footing with the number of schizophrenics in the general population.

Page 39

Appendix E: The Shy Bladder Center (SBC) and the American Restroom

Association (ARA)